The Age of Dread

I’m Umair Haque, and this is The Issue: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported publication. Our job is to give you the freshest, deepest, no-holds-barred insight about the issues that matter most.

New here? Get the Issue in your inbox daily.

How are you feeling these days? Me—I’ve been waking up with a strange, heavy feeling. Sometimes, panic rouses me. Mornings are disorienting. The news—I don’t check until I’ve had coffee, taken Snowy for a walk, and had plenty of time to think and reflect. And, as I pondered, to ground myself. Steel myself, maybe.

I wondered and wondered. What is this feeling that’s begun to…plague me? I’ve begun to feel tormented by it, if I’m honest. Maddeningly, I couldn’t name it. A kind of upset, in a vague, diffused sense. Existential…something.

I asked around. Friends. Elders. Relatives. How are you feeling? No—really feeling. You see, I’ve been waking up with this…heaviness. Almost a kind of vertigo. As if there’s a cliff ahead of me, beckoning. And I feel…

Many of them said: I feel just that way, too. And it’s understandable. The world has gone off the rails. We live in a time that has many names, no names, all the names. Trouble, hate, spite. Oblivion is where things seem to be heading. The ship of civilization appears to have no caption, no rudder, a broken sail, and is listing steeply into the wind. The waves batter it. The passengers?

Add up the macro trends we discuss so often, which are at the core of what you might call the analytical project I do here. They’re all incredibly dire. Democracy, imploding—like never before in history. No, not “even” the 1930s, really, because of course democracy then was less advanced and widespread and sophisticated to begin with. The global economy, stuck in stagflation, heading into a lost decade…and then what? Climate change, the elephant in the room that—to mix metaphors—we brush under the rug, until it’s summer again, and then the mega-scale impacts return, with a horrifying vengeance. I could go on—this is a portrait, in short, of a civilization on the brink. All the names, so many names, not enough names. Of ruin, beginning to surround us.

And overwhelm us.

I took some time to read. And read. And read. What was this feeling? This vertigo, this heaviness. After a time, I realized, there was a kind of fog before me. Uncertainty, diminishing the sure horizons of what used to be a future into a pale, grey mist.

And what did I feel about all that? Dread.

When I understood that, at last, things finally snapped into focus. I went back to my friends, relatives, elders, cousins. We talked a little more. This feeling so many of us were—are—experiencing. Fear—not rich enough a term. Anxiety—far too much an understatement. Despair? Not quite. All close, in a way, but none really captured it. Until…dread.

This is the Age of Dread. When history looks back on this age, it will see what we don’t: a shockwave of dread sweeping the globe. After I came to that little epiphany, I began to see it in all the statistics, too. The majority of young people feel “numb,” “completely overwhelmed”—way, way beyond mere anxiety. Yet it’s not just a kind of simple despair, either: the majority of young people worldwide—a bullet of a statistic we’ll discuss more in depth—think “humanity’s doomed.”

Pause and think about that for a second. The majority of young people around the globe think humanity’s doomed. Of course, then, it makes sense that we see startling numbers like the majority are numb and overwhelmed and can’t function. That’s dread.

Dread goes beyond mere anxiety in many ways. Anxiety’s a feeling of uncertainty. The experience, perhaps, of a sense of danger. Dread is different: it’s a kind of knowing. That things won’t be right again. That worse is sure to come. It’s not uncertainty, in that way, but more the horrifying realization of certainty—the negative kind, carrying the message that…

Carrying many, many messages, if we examine it carefully. If dread says: “I know things will get worse,” it also implies: “perhaps there isn’t much I can do about it. I’m a hostage, a prisoner, in a way, of forces far, far greater than me.” And so with dread comes a profound experience of powerlessness, loneliness and hopelessness.

Think about that, too, for a second, and tell me those precise currents aren’t sweeping through our societies. We speak openly of “loneliness epidemics.” There’s the open sense of contempt and disgust towards institutions—speaking to people’s sense of powerlessness. And as people turn to hopelessness, of course, conspiratorialism begins to rot minds, social ties sunder, demagoguery rises, and the finger’s pointed at scapegoats, out-groups, and other innocents, to redirect the rage, fear, and fury.

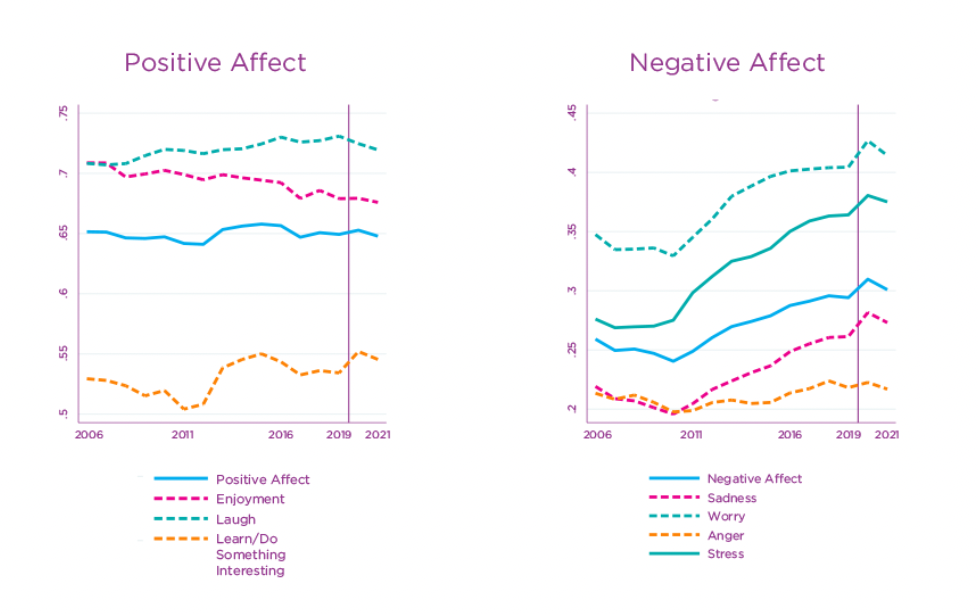

Pause to consider what I call the Most Important Chart of the 21st Century, below. The one I sum up as The Modern Crisis of Being—it shows happiness flatlining and falling, in all its components, while unhappiness in all its components, fear, anxiety, worry, despair, explodes off the chart over the last decade and more. Isn’t that a portrait of intense dread? And not just that—but dread surging around the globe?

These feelings—powerlessness, hopelessness, and loneliness—are some of the most powerful that a human psyche can experience. But that’s hardly what we’re going through. We’re going through this collectively. Many of us—the vast majority of us, according to every single statistic there is, really—says we’re all experiencing this at once. Humanity is having something like a collective dread spiral, in other words.

And it’s accelerating the destabilization of everything. Dread makes polities more unstable, turning people to lunacy, fringe movements, authoritarianism. It sucks the confidence out of economies, crucial to their functioning. It rips the optimism away from societies, turning social groups against one another, unmooring trust in institutions, sundering ties and bonds. And it does something deeper, too: it turns us numb. It produces a kind of lethargy, a sort of passivity, a resignation to fate. Because, after all, dread isn’t just a feeling—but a knowing.

This is where we are. But where do we go? What are we to do with all this? To really understand it, I think, we must go one step deeper still.

Dread comes from a place of ontological insecurity.

You can read that link, and it’s not bad, but I’d offer a slightly definition than the one therein. Ontological insecurity. Ontology: the nature of being. Insecurity: the nature of my being is no longer secure. In these times? People feel as if they have no future. Their economic beings are at profound risk, after years of a “cost of living crisis” that isn’t going anywhere soon. Their political beings, too, are at risk, as democracy implodes. Their social beings, too, are being diminished, withered away, whether by technology, the loss of social bonds, the slow death of civil society as a vibrant thing you live in and among, as a trusted equal, not a bitter enemy in an endless combat to the death at the end of capitalism.

The Modern Crisis of Being, I’m coming to understand, is greater and graver than I thought, when I began to write about it. It goes all the way deep—right into the heart of being itself. Being as ontology, in the sense of: who am I? Why am I here? Take security, stability, a future away—and it turns out, perhaps unsurprisingly, that people will accept poorer answers. I’m here to hurt them. I am here to obey the Authoritarian Father who alone can protect me. In this uncertain universe, of moral betrayal, I am vengeance. I am the purification and the last judgment.

All this is what happens when a civilization’s well-being goes into sharp, steep decline, as ours has. Earlier, before, I’d put it this way: when well-being falls, destabilization results. But perhaps, I think now, that’s too superficial a way to put it, failing to really cut to the heart of the human experience. When well-being falls, this sharply, this steeply—remember the macro trend I call the Great Divergence—suddenly, people’s ontological sense of certainty, surety, their place in the universe, seems ripped away. They don’t know how to be anymore. Who to be. Why to be.

And that opens the closest thing we have to Pandora’s Box. Along can come lunatics and demagogues, telling them who, why, what to be. Systems of control can offer them certainty and stability, if only they’ll give up freedom and democracy. Economies lurching out of control offer them meaningless exploitation, in return for a fleeting hit of power, a dopamine rush of supremacy, status, esteem, with which to numb the pain away. Who am I? Why am I? I was a citizen once, a member of a civilization, a moral and social agent, an equal, a fellow traveler in this journey called history.

I am reduced. I am shrunken. I am withered away. Powerless. Hopeless. Alone. All I feel is dread. Who am I now? Why am I now? I am vengeance. I am hate. I am the sword delivering moral vengeance to those who have wronged me. I put the moral universe right again, my place atop it, supreme, through this ritual sacrifice. Here I am. Nothing. Everything. The beast in the man, and the man in the beast.

Pandora’s Box. What was that myth about? All woes flew out of that vessel: misery, strife, disease, violence, even death. Pandora, the first woman, was instructed by Zeus, never to open the box—originally a jar. Her curiosity got the better of her. See the resonance to the Tree of Knowledge, in the Garden? Trapped in the terrible pain of existence, we humans must always hope. Despite the sure knowledge of what we inflict on one another. And in all that, we find ourselves at this eternal turning point, where we stand once again.

The dread overwhelms us. Can you feel it? This is what it feels like when a civilization’s collective heart stops in panic. Yet in that dread, too, lies the burning message of the box: it’s the surety of woe that defines our truest purpose and worth. Damned as we are, our duty is to fulfill life’s highest promise to itself.

❤️ Don't forget...

📣 Share The Issue on your Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them all all about it.

👂 Anything else? Send us feedback or say hello!

Member discussion