The Supreme Court, Trump, and the Final Nail in Democracy’s Coffin

I’m Umair Haque, and this is The Issue: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported publication. Our job is to give you the freshest, deepest, no-holds-barred insight about the issues that matter most.

New here? Get the Issue in your inbox daily.

Quick Links and Fresh Thinking

- The institutions of government aren’t going to protect democracy (A must read.) (WaPo)

- It’s Past Time to Quit Hoping the Courts Are Going to Stop Trump (Slate)

- The Supreme Court Just Blew a Hole in the Constitution (New Republic)

- The Supreme Court Must be Stopped (The Nation)

- Takeaways from Trump's historic Supreme Court win (CNN)

- Europe gets ready for war (El Pais)

- Making Sense of Society (Project Syndicate)

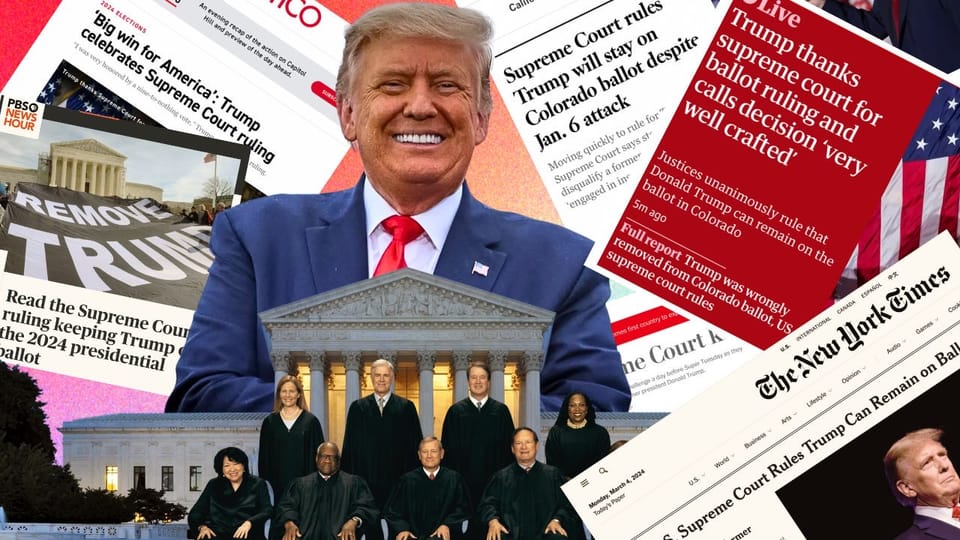

By now, you’ve heard. The Supreme Court ruled for Trump—unanimously, no less. Let’s cut to the Post’s excellent summary, and then get to the meat of the matter.

The justices said the Constitution does not permit a single state to disqualify a presidential candidate from national office, declaring that such responsibility “rests with Congress and not the states.” The court warned of disruption and chaos if a candidate for nationwide office could be declared ineligible in some states, but not others, based on the same conduct.

“Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos — arriving at any time or different times, up to and perhaps beyond the inauguration,” the court said in an unsigned, 13-page opinion.”

What really happened here? Here’s the opinion itself.

Here are my six takeaways.

1. The Supreme Court evaded the question—and abrogated its key responsibility, too—by leaving democracy no remedy for insurrection.

Is someone who broke their oath of office and led an insurrection disqualified or not? According to the Supreme Court, States can’t make that decision—only Congress can.

Never mind the obvious hypocrisy of “chaos” breaking loose if a candidate were disqualified—versus that of precisely the same candidate openly promising to install a dictatorship. Which is worse? Never mind, too, the rank hypocrisy of “states rights’” for some issues, but none for this much more fundamental and central one. Which counts now?

2. America’s now in a constitutional no-mans’ land, a crisis.

There’ll be the kind of person who says “let’s decide this at the ballot box! It shouldn’t be decided judicially.” They’re wrong, not as a matter of opinion, but as an institutional matter. If States aren’t.

How precisely is Congress to enforce Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which is what all this hinges on? Remember, Section 3 says, explicitly, someone who violates this, attempts a coup, is disqualified. It doesn’t mince words. So what’s the Court’s actual remedy to all this?

In their decision, the Court says: “Shortly after ratification of the Amendment, Con- gress enacted the Enforcement Act of 1870. That Act authorized federal district attorneys to bring civil actions in federal court to remove anyone holding nonlegislative of- fice—federal or state—in violation of Section 3, and made holding or attempting to hold office in violation of Section 3 a federal crime.”

So in other words, the Supreme Court is saying that Congress decides this issue legislatively—it’s a federal crime to violate Section 3.

But there’s a big problem with that.

Even that doesn’t disqualify a person from running for office. As we all know by now, even if Trump’s convicted in his insurrection case, he’s still probably allowed to run for President again, and assume the office—and worse, this judgment only confirms all that. But that’s precisely what Section 3 says, extremely clearly, and we’ll come to that in a second.

In other words, the Court’s remedy isn’t actually a remedy. Violate Section 3, maybe you’ll go to jail, but the problem—can you hold office again?—isn’t remedied at all, in the slightest. And in this sense, of course, justice isn’t done, which is the point, wait for it, of a judiciary. (And no, “jail time” isn’t a remedy in question, we’re not just talking “punishment,” but “remedy,” as in, solving the problem, remedying the wound to democracy itself.) If you can still be President from jail…we all know that the remedy doesn’t actually matter and isn’t one.

So who can actually disqualify someone who’s violated Section 3 of the 14th Amendment from holding office? According to the Supreme Court, nobody can. States can’t. The Supreme Court can’t. And Congress can’t either—beyond legislation, what exactly is it to do? That’s it’s role in government institutionally, after all. Is it to issue a Special Edict? Assume Special Powers? What does that even mean?

So if you ask me, the Supreme Court has failed, and failed badly. I’m not even on the side saying that Trump should be automatically disqualified, as a matter of political opinion. But I am saying the Supreme Court has said nobody can disqualify anyone else from holding office. It has effectively said that there is no institution which can enforce Section 3 at all.

Not States, explicitly, not some kind of referendum, only Congress, but wait, even being convicted of precisely that federal crime doesn’t disqualify someone from office. So where does that leave us?

In an institutional Twilight Zone. In a Kafkaesque maze. A nowhere-land. If no institution of governance can act to make Section 3 real, does it exist at all? And this is precisely the outcome that authoritarians tend to want—vagueness, a cloudiness, a lack of clarity, so that the rules can always be bent to their will.

What’s the Point of a Judiciary?

Section 3 couldn’t be more explicit.

See how clear that is? Does the constitution matter, or not, or only sometimes?

That leaves us with one possibility, that Congress could maybe enforce Section 3 through a vote. But what kind of vote?

If the only way that Section 3 can be enforced is through, let’s say, a Congressional vote, then of course, that’s the weakest guardrail against authoritarianism imaginable, because in such a situation—insurrection, coup, overthrow—presumably, there’s a pretty good chance such a vote would be tainted to begin with. “Votes” of such kinds aren’t laws or rules, and what constitutions are supposed to give are laws and rules—permanent lines, not temporary, shifting ones.

Section 3 is interestingly explicit about what it’d take to “remove the disability” of disqualification—a 2/3 vote of each house. But even more interestingly, it’s not explicit about what it’d take to disqualify someone in the first place. That’s a pretty good tell that the only enforcement mechanism of this amendment wasn’t just meant to be Congress, because of course, if it was, then presumably, it’d just stated so as clearly for disqualification as it does and did for disqualification. That’s a bit abstruse, but I think you see my point.

Imagine now the opposite. What if Congress, reading this ruling, sighs, and decides—we all know it won’t, so just imagine—that a 2/3rds vote can disqualify a candidate, like a Trump? Of course, then said candidate could just challenge it, appeal to the Supreme Court, who, given this reading of affairs, would just as likely say: nowhere does the constitution give Congress the power to do that.

So however we read this ruling, the Supreme Court is saying: nobody can be disqualified for office, by any institution, in practice, full stop. That’s an incredibly foolish and dangerous thing for a Supreme Court to say, and we’ll come to why. First, though…

Constitutionally, Section 3 is as clear as it gets. Someone who breaks their oath and engages in insurrection is disqualified.

The Supreme Court has said: maybe, maybe not. It’s not up to us to say. It’s up to Congress to say. But nowhere does it say such a thing in the constitution itself, which of course shreds the notion of “originalism” so beloved of the fanatics on the court. We can’t answer that question, says this Supreme Court. Maybe it’s Congress, maybe it’s the Department of Justice, maybe it’s someone at the federal level. But who? How, precisely? In what way? And why isn’t it the judiciary?

3. In this way, the Court’s ducked the central question: why isn’t it the judiciary’s job to disqualify candidates? Is that how democracies should—and indeed, do—work?

The Supreme Court have laid out plenty of options. It could have established criteria for what an insurrection is, what the bar for disqualification is, and asked States to present evidences that rises to that level. It could have specified a number of ways to enforce Section 3, or at least a number of possibilities, and sent the issue back to Congress, or the Department of Justice. It didn’t do any of the above. Instead, it basically said, and this is takeaway number three, and I guess it’s the big one…

4. The Supreme Court didn’t just say “Trump’s qualified.” It went much further, and said effectively said that nobody can be disqualified from office, by any institution of governance, no matter how grave their abuses of power are.

What is a Well-Designed Democracy?

Let’s examine a bit further what the Supreme Court’s really saying here. Who should decide whether or not a candidate’s qualified for office? That’s a primary function of a democracy. The Supreme Court’s saying that judiciaries shouldn’t decide that question, and that legislative bodies should, like Parliaments or Congresses.

That’s a poor answer in democracy’s own terms, too, given what we know about democracy. In a well-designed democracy? It’s exactly the judiciary who should decide who’s qualified for executive office or not. Not Congress or Parliament. Why? Precisely because Congresses and Parliaments are governed by parties, but judiciaries are, at least nominally, not explicitly politically aligned. When we say that “Congresses and Parliaments should decide who’s fit to be in the executive branch,” the conflict of interest, when you think about for the merest moment, couldn’t be clearer: all kinds of problems of party politics quickly emerge. That’s why in most well-designed democracies, it’s never Congresses and Parliaments who decide on the executive branch, and if they do, it’s a position less important than head of state.

So to say “the judiciary shouldn’t decide this matter” is an incredibly foolish stance to take. It’s exactly the job of a judiciary to check the fitness of both executive and legislative branches, decide on qualification and disqualification, because, well, who else is going to do it? Asking executive and legislature to merely check one another is simply asking for trouble and dysfunction.

“Banana republic” politics is badly misunderstood by a lot of Americans. In “Banana republics,” the last bulwark and semblance of democratic rule comes down to the judiciary. Precisely because there, badly designed democracies mean that executive and legislature, working hand in hand, unable to check one another, end up in bed together instead, and proceed to loot the country.

5. America’s Supreme Court’s not exactly a set of the sharpest tools in the shed—but for it to be this ignorant about what a well-designed democracy is, and how one works…where judiciaries can and do decide fitness-for-office issues, not legislatures…that’s breathtaking.

Again, I’m not saying Trump should be disqualified. But I am saying that a society which can’t answer that question—in which nobody can be disqualified from office, and their abuses and crimes simply don’t matter anymore…that kind of society is already ceasing to be a democracy. Because of course a democracy is founded on the rule of law, for which constitutions lay foundations, and assign powers to branches of government.

But when a judiciary decides that a constitution’s amendments, clauses, powers don’t matter—that no institution can enforce them, then it’s saying: they’re simply theoretical. They don’t exist in reality. As matters of actual governance, versus some kind of numinous philosophy, they can’t be acted upon. In this case, by saying only the legislative branch can check the executive branch—and the judiciary can’t and shouldn’t—but wait, the legislative branch can’t do that in practice, America’s Supreme Court is saying that all this is just academic anyways.

And in that sense, such a judiciary is also saying that democracy doesn’t matter, because then neither do constitutions. If a judiciary can’t decide on what the powers of a branch of government are, how is a democracy to function? If it simply says that a power clearly delineated in a constitution doesn’t exist in practice, then what sort of slippery slope are we on, exactly?

I’d be happier if the Supreme Court had at least given us something to debate, discuss, chew on. Don’t want to disqualify Trump—sure, don’t—let’s get real, this court was made for him by him. But this is the worst outcome of all. Section 3 doesn’t matter, and the 14th Amendment is nice in theory, but in practice, hey—sorry, doesn’t really exist.

Is that still democracy? I don’t know, but it’s at the very least an extremely slippery slope.

6. This is one of the final nails in American democracy’s coffin, if you ask me.

Trump v Anderson is a case that’ll define history. It’ll be remembered, if I had to bet, as the moment that sealed America’s fate, which looks, if the election were held today, and any day in the last few months, increasingly like a Trump Dictatorship.

This Supreme Court will be remembered as the worst sort of judiciary—not just the kinds that enables authoritarians, which are penny-ante, but as the sort who turns their backs on the sacred principles that bind us together in this project called civilization. That constitutions are documents of consent, which join people together in unions, and violating them is a grave offense precisely because it offends us all, history, futurity, the present, democracy itself. For none of that to matter is quite something.

I know those are harsh words, so reconsider again, that I’ve never been emphatically on the side of disqualifying Trump. But to see the answer to that question becoming: we won’t disqualify him, in fact, we’ll just ignore the ideas of constitutuonality, law, and consent, and say that nobody can be disqualified for anything, period, nah, nah, nah, here we are, thumbing our nose in your face like babies.

It’s childish. This level of illogic? This absolute? Even kids would probably do a better job of doing their jobs. It makes no sense, though, because making sense in this case doesn’t matter, and thumbing their noses at the rest of us, at history, at the world, at democracy is what does

This judgment? It’s a clear a statement you could have about what contempt really is. For…everything but raw power, asserted to the point of violence. The Justices aren’t just nailing democracy’s coffin shut. They’re kicking them in, with scorn. There’s the sense of a sneer in all this, for even asking the question, and in return, an angry scowl, here’s how little your precious democracy matters, and then a grin: see what we did? Now nobody can do what you asked.

We took away that power entirely, the very one you wanted. From everyone. Poof, gone. Nah, nah, nah. Thumb-face. Suck on this, losers. You wanted it decided? We decided. Not yes or no. We went much further than that. By saying that it doesn’t really exist and never did.

So all this, my friends? This is a terrible way for democracy to die. In disgrace, pitilessly, bereft—abandoned, in the end, even by those were to be its very guardians to the last.

❤️ Don't forget...

📣 Share The Issue on your Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them all all about it.

👂 Anything else? Send us feedback or say hello!

Member discussion